This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

The U.S. economy is actually doing pretty well. But for working people navigating mixed messages and high prices, the dominant feeling has been meh.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

Feeling Iffy

“US. ECONOMY ADDS 400,000 JOBS IN MONTH: REPORT SPURS FEARS, declaimed the Washington Post last February … APRIL JOB GROWTH EASED DECISIVELY, STIRRING CONCERN, the New York Times warned … By June the Journal was warning, SOFT LANDING MAY BE THREATENED BY CONSUMERS.”

You would be forgiven for assuming that the above headlines are plucked from this year’s newspapers, but they’re actually more than 30 years old. These were gathered—and skewered—in a 1989 article in The New Republic titled “The Sky Is Always Falling,” in which Gregg Easterbrook argued that newspapers frame all economic news, even seemingly positive developments (job growth, for example), as bad news.

A similar tendency appears in many of today’s reports on the economy too. To be fair, the sky does often appear to be falling, and sometimes for good reason: A lot of the recent economic news is self-evidently bad. But although inflation has been a beast, the economy is actually doing very well by some metrics. Unemployment is low! America has added jobs 31 months in a row! Consumer spending is high! Many economists and Fed officials, until recently, have been reluctant to cheer for these apparent wins, fearing that a tight labor market and strong demand would lead inflation to persist. (When it comes to economic data, it seems, all signs can turn out to be bad signs in retrospect.)

Consumers, too, have been feeling meh for some time now. In June 2022, consumer sentiment reached its all-time historic low since the University of Michigan began measuring it, more than 50 years ago. And a New York Times/Siena poll released this month found that just 20 percent of Americans think the economy is good or excellent. But spirits seem to be lifting: Data from the University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers indicate that consumer sentiment has trended upward this summer and is now closer to the average outlook during a standard year for the U.S. economy (if still not quite there). This metric matters because when consumers feel confident, they spend more on goods and services—and, in turn, serve as the engine of the economy, Joanne Hsu, the director and chief economist of the University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers, told me.

Americans’ lukewarm feelings about the economy over the past year make sense in many ways. Inflation has been higher than it’s been in decades, hitting many younger working people for the first time. And until late this spring, hourly wages had been outpaced by inflation for two years. Consumers feel poorer. “As an economist, I would say [the economy] is pretty good, because I’m optimistic that there is going to be further real-wage growth,” Darren Grant, an economist who has studied consumer confidence, told me. But, he added, as a working person who has seen his purchasing power diminished by inflation, he understands why many consumers don’t feel that same optimism. (It’s worth noting that average real wages have crept up in recent months, and many workers did see gains last year—especially those who switched jobs.)

Perception also plays a role in consumers’ iffy views on the economy; as my colleague Annie Lowrey wrote last month, “Consumers tend not to notice when things get better as opposed to worse.” Further exacerbating negative perceptions is what she has called the Wrong-Apartment Problem, or the fact that so many people can’t afford to live where they want to live, which can strengthen the sense that the economy is in a bad place. And political leanings can also color how people feel about the way things are going (anti-Biden Americans might not be enthusiastic to embrace “Bidenomics”).

The information environment we live in is not conducive to fostering great vibes about, well, anything, but especially about the economy. For more than a year, a drumbeat of headlines have warned that a recession is imminent. And consumers are inundated with information—not always accurate—on social media. Nearly half of Americans said earlier this summer that they thought the country was in a recession or would be in one soon. Nearly half! “The discourse around the economy is very different than it was 40-plus years ago,” Hsu told me. “The share of people saying they’d heard bad news about inflation was much higher over the last year than it was in the ’70s and ’80s,” when inflation was higher. Though the news environment is not necessarily the cause of recent negative feelings about the economy, she said, it likely reinforces them.

The story of the economy right now is one of mixed messages and mixed reactions. Grant explained that we’re in a “middle zone,” where people are watching some economic measures improve as wages catch up. Inflation is still not quite where the Fed wants it to be. But, hovering around 3.2 percent, it’s much lower than it was last summer, when it peaked above 9 percent. And in the second quarter of the year, the economy grew by 2.4 percent, surpassing expectations. What the Fed and many economists now hope to see is a growing, but not rollicking, economy. So far, it seems that the U.S. has managed to achieve lower inflation without a ton of people losing jobs. That’s legitimately good news.

And, as the preliminary data show, consumers are recognizing that. “The public has a pretty reasonable sense of what’s going on in the economy,” Grant said. “We should give them some credit.”

Related:

Today’s News

- President Joe Biden will travel to Maui on Monday as the island continues search, rescue, and recovery efforts following severe wildfires.

- A forest wildfire on the border of California and Oregon, in the same area as a deadly fire last year, has led to evacuation orders.

- Despite Russian attacks, vessels transporting Ukrainian grain have been able to travel through a Romanian, NATO-protected lifeline.

Dispatches

- Up for Debate: How should liberal democracies utilize or eschew taboos? Conor Friedersdorf asks readers for their views.

- The Weekly Planet: Here’s how one scholar turned her house into a zero-carbon utopia.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

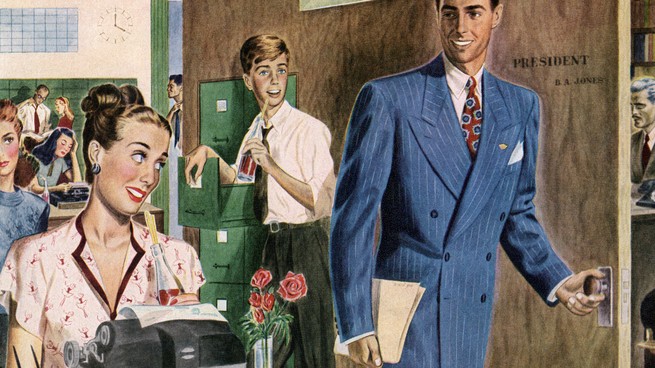

The Bizarre Relationship of a ‘Work Wife’ and a ‘Work Husband’

By Stephanie H. Murray

It started out as a fairly typical office friendship: You ate lunch together and joked around during breaks. Maybe you bonded over a shared affinity for escape rooms (or board games or birding or some other slightly weird hobby). Over time, you became fluent in the nuances of each other’s workplace beefs. By now, you vent to each other so regularly that the routine frustrations of professional life have spawned a carousel of inside jokes that leavens the day-to-day. You chat about your lives outside work too. But a lot of times, you don’t have to talk at all; if you need to be rescued from a conversation with an overbearing co-worker, a pointed glance will do. You aren’t Jim and Pam, because there isn’t anything romantic between you, but you can kind of see why people might suspect there is.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. Matrimony can prompt questions about freedom, desire, and identity. Here are seven books that explore how marriage really works.

Watch. Murder, She Wrote (streaming on Peacock) is a timeless and cozy whodunit series.

Katherine Hu contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.